The Saga of the Crew of Liberator 568

The following is from the 456th history book, page 51.

747th Squadron

by Al Miller, Pilot and James Parson, Navigator

Our crew all met each other in the early spring of 1944 at Muroc Army Air Base in the blowing dust and sand of the California desert. This base later became Edwards AFB, where the space shuttles are now landed.

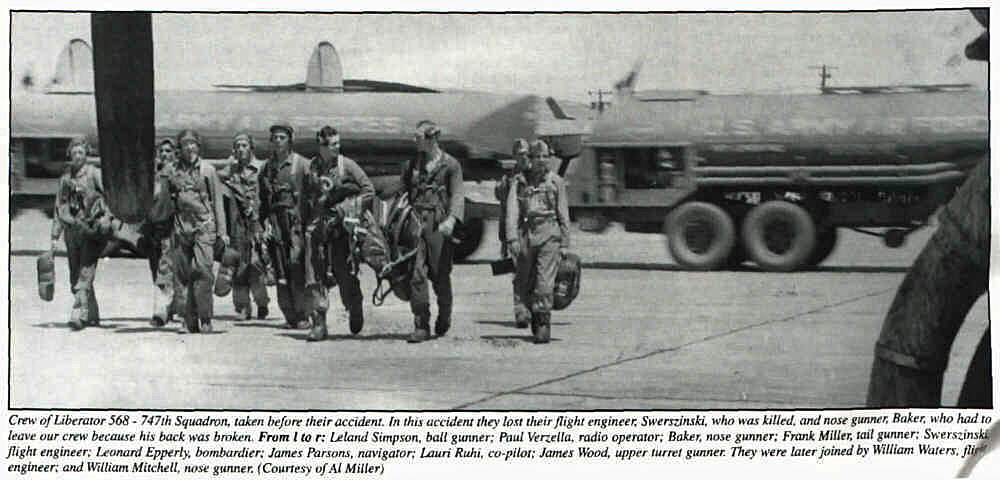

The photograph of our crew (below) was taken at this base before our accident. In this accident we lost our flight engineer, Swerszinski, who was killed and the nose gunner, Baker, who had to leave our crew because his back was broken.

Pictured left to right are: Leland Simpson, ball turret gunner, from Barnhill, IL; Paul Verzella, radio operator, from Hookstown, PA; Baker, (first name and hometown unknown), nose gunner; Frank Miller of Portland, OR, tail gunner; Swerszinski, flight engineer, (first name and hometown unknown; Leonard Epperly, bombardier, Fayetteville, AR; Al Miller, pilot, Bakersfield, CA; James Parsons, navigator, Lynwood, NY; Lauri Ruhi, co-pilot, Iron Mountain, MN; James Woods, upper turret gunner, Little Rock, AR. We were later joined by William Waters, flight engineer, Cochituma, MA; and William Mitchell, nose gunner, Fort Seybert, WV.

Our operational training in bombing, gunnery, navigation, and emergency procedures progressed rather smoothly until late one night near the end of our training period, when we were returning from a long navigation mission. As we were letting down to turn into the traffic pattern at our base, we suddenly lost all four engines and crash landed in the desert in less than one minute's time. We were flying a brand new airplane just built in San Diego that had the fuel system improperly installed. It is probably not necessary to say that afterward we were leery of new airplanes. (The complete story from the differing perspectives of four of the surviving crew members can now be read at this link: Muroc Crash).

About a week after this horrible ordeal, we were on our way to Hamilton AFB, near San Francisco, California, to pick up a new Liberator and start our trip to our combat assignment. We officers had an experience there when we walked into a beautiful officer's club and were settling in for some quality R&R, when we were approached by an old major who told us that we were not allowed in there. He said that we were transients and that our club was down at the end of the runway. This turned out to be another plywood and tarpaper shack like we had just left in Muroc. We vowed then and there that we wanted to fight a good war to preserve the life style of the wonderful old officers of Hamilton AAB.

Within a couple of days we were on our way east in a new Liberator, which sort of verified our distrust of new airplanes. This new airplane sort of flew cross-wise and was very sluggish. We stopped the first night in New Mexico, the second night in Tennessee, and the third night in Bangor, ME.

In Bangor, ME, we received orders which were sealed and we couldn't open them until we were airborne the next day, so we lay awake at night wondering where we were being shipped to. We concluded that it had to be a European Theater, since we were in Bangor, ME, headed east. Next morning when we were in the air we found we were headed for Italy and were not all that disappointed, since we hadn't heard about too many bad things happening to bombers in Italy. Our next stop was Gander, Newfoundland, where we were warned to watch out for moose on the runway. The next day we started out in a flight of 30 bombers heading for the Azores. This was one of the toughest flights we ever had. We were assigned an altitude of 4,000 feet and flew through a half dozen north Atlantic weather fronts and never saw the sky or water during the whole trip. We would have never found the Azores Islands without a very excellent radio direction finder which picked up the Azores station from some 600 to 700 miles away.

When we arrived at the Azores, the weather was still horrible with ceilings of a few hundred feet. We also learned about two crashes of airplanes just ahead of us who were attempting to land. Because there were some 30 airplanes who had to get onto that field, and our fuel was getting low, we decided to take some drastic action. We headed out to sea on reciprocal heading and let down to the water level under about a 200 foot ceiling. We then turned around and flying on the deck, followed our trusty radio direction finder toward the airfield. Lo and behold, we came upon the end of a runway on which we promptly landed without introducing ourselves or getting permission. Things were so chaotic there, we must have got lost in all the confusion and were completely overlooked.

While at the Azores we learned about the rats that lived in the stone walls that were all over the place, rats that carried typhus germs and bit people so we were glad that we had had shots with everything that they could stick into us before we left the States.

Since the Azores was a neutral country, German planes were allowed to land there, too, and there were some at the other end of the runway. Now we wondered why our orders were sealed and such great secrecy about our whereabouts was so important, when here were the Germans sitting there counting us as if we were sheep going to the slaughter.

Our next stop was at Marrakech, Morocco, where we saw some French Foreign Legion soldiers guarding Italian prisoners of war in a fenced-in enclosure. The prisoners lived like pigs in a pen. Their food and water were put into troughs, and their only shelter was as brush arbor at one end of the enclosure. We decided that this life style was definitely not for us and was something to avoid if at all possible.

Our next destination was Tunis, Tunisia, where we saw almost total devastation of the airfield buildings, and the runway bomb craters had just been freshly repaired. Now we knew we were getting close to a war. From there we flew to Italy by the way of the island of Sicily, where we saw war ships by the hundreds (maybe even thousands), which led us to believe that there had been, or was going to be, a big show somewhere. A day or two after arriving at the 456th Bomb Group, 747th Squadron, our pilot flew his first mission a co-pilot with another crew supporting the invasion of southern France. Here he saw all of those ships again.

When we arrived at the 456th Bomb Group, we were assigned a brand new shiny, silver Liberator, #568. This plane was better rigged, flew faster, and was more agile than the one we had brought from California and left at a staging area. Discussions soon started on what to name our plane and what kind of nose art we wanted to paint on it. This went on for a while and we flew a few missions. After a pretty tough one (that we came out of unscathed), we got superstitious and figured that if we painted anything on good old 568, something very bad would befall us; so for the rest of our war, we kept our airplane as clean as a whistle.

We did have some problems, though, having our hydraulic system shot out near Vienna, coming back to make a tail-dragging, ground-looping landing. Our plane and our crew came out of this ordeal okay, except for the radio operator, Paul Verzella, getting a sprained back slipping around in the hydraulic fluid. Several of our crew received decorations for the parts they played in this episode.

Later we had another problem near Munich, when a shell went unexploded through our wing and dropped all the fuel out of our tank for an outboard engine. We carefully nursed our plane back and landed at the first field we spied after getting past the Po Valley, which was still held by the Germans.

We finished our missions in early January 1945 and headed back to the States.

We came back by sea, on the USS America, which was a beautiful ship, with wonderful food, though we only got two meals a day. We sunbathed up on the deck in the Gulf Stream the day before we landed in Boston. When we disembarked for the next morning, the ship had three or four feet of ice all over the superstructure. It was 20 degrees below zero outside with snow everywhere. Even so, we were very glad to get on U.S. soil, and the coffee and doughnuts the Red Cross served us standing there in the snow, tasted much better than the ones we got at the 456th at the end of a mission!

This is the last time we saw each other in uniform, and it was a bittersweet parting for a wonderful, courageous crew, who had fought their war and returned to tell their stories to whomever would listen.