Muroc Crash

This page contains the words of the four members of Al Miller crew regarding their harrowing ordeal during training at Muroc Army Air Field. In the very early hours of 4 July 1944 while on a training flight their B-24 Liberator suddenly lost all four engines while going through approach descent at no more than 1000' altitude - and within seconds was crashed on the desert floor.

The words of James Parsons and Paul Verzella came in the form of a letter at Al Miller's request. Al provided his recollection directly when in January 2002, as did Frank Miller (no relation to Al).

It is remarkable that the injuries to the crew were not greater. And it is also remarkable that these men remember the same event so differently.

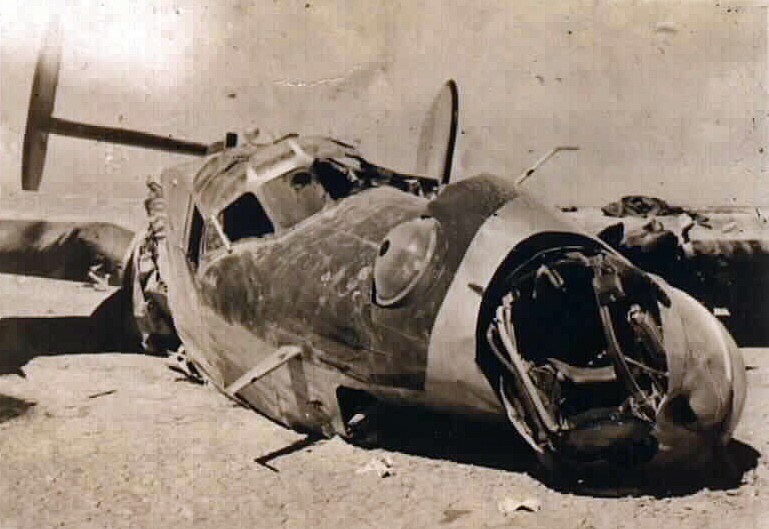

The picture above of the crashed B-24 was provided by Al Miller.

First up is Al Miller:

The Pilot's recollection of his Miller Crew’s crash of their Liberator at about midnight, July 3, 1944 at Muroc, California.

We were returning from a high altitude celestial navigation training mission and letting down to enter the traffic pattern at 1500 ft. when we lost all four engines and crashed in probably less than one minute. This mission did not involve much from the crew except me and the navigator so the fuel gages probably did not get much attention.

When the first engine quit, the engineer jumped into action and the co-pilot and I watched the fuel pressure gages go to zero one after the other. All four engines were wind-milling and we were dropping like a rock. We had no time to do anything except to try to make our contact with the earth as soft as possible. I went for the flaps and the co-pilot the wheels and the landing lights. Before anything was deployed we had hit Mother Earth. About all we accomplished was to keep the wings level and the airspeed above stall speed. It was dark and not possible to judge how far above the ground we were.

We pancaked her into the ground very hard and broke the fuselage in two places. The top turret came loose and slammed down on the flight deck. When the dust had cleared, I found the co-pilot had not fastened his seatbelt and his butt was sticking through his windshield. This turned out to be a good thing – he and I got out through that hole.

Our engineer made his last gasp and died when his head busted open as it hit the throttle quadrant. He was running between the fuel gages and valves and the throttles and pressure gages. He was making a valiant effort to bring some life back to those engines. We will never know if he had a clue as to why we were not getting any fuel to the engines.

We had two engines on fire, but thank goodness they were oil fires. Our bombardier was in the back of the plane and jumped out a waist window, got the fire extinguisher and put those fires out pronto. We still had one third or more of our fuel on board but we did not rupture a fuel tank or break a fuel line. Had this happened, we would have been fried.

The flight deck behind the pilot’s seat was a terrible mess. The top turret was down and the radio operator, navigator and two gunners were pinned in there. The rest of the crew was in the waist window area and were okay and the first to get out. They broke the plexiglass out of the top of the top turret and the navigator, radio operator and a gunner crawled out through this hole. The gunner with a broken back and the dead engineer were taken out by the rescue crew that came out from the air base.

Our bombardier ran all the way (probably four or five miles) to the air base to get help. When help started coming from the base we could see headlights fanning out in every direction. Our radio operator set fire to my parachute and they all headed towards us. Of course, I did not return this chute I had checked out, so a bill was given to me every time I changed stations. I had to tell this crash story every time to keep from paying.

Why all four engines quit at the same time was not determined before we left for overseas. Every pilot, engineer and engineering officer I ever talked to had theories and all boiled down to that the engines were sucking air or nothing. But where was the air or nothing coming from? Another factor was that we were flying a new airplane. Was it’s fuel system installed correctly?

The losing of four engines at the same time happened to the Mapa Crew of the 747th. They were flying the Lady Corinne about the same date. Their episode happened coming off a target at 21,000 ft. They lost 18,000 ft. before they got them running. Again, aircraft commander John asked everybody and did everything he could to find out why but never did.

If there was a hero that emerged from this tragic episode it had to have been Lt. Leonard Epperly – our bombardier. He put out the engine fires (he could have run away to a safe place), he helped break the plexiglass out of the top turret so three men could crawl out and ran four or five miles in his sheepskin boots and blistered his feet to get help.

What was his reward? He got to go overseas and fly thirty-five combat missions and come back to the states only to be killed in a bombardier’s training plane on a sunny day in Texas. Many of us on our crew tried to find why this happened but no one could find out anything. It all seemed to be a mystery. Wars abound with the unexplained!

Al Miller, Pilot

The next memoir of the incident is from James Parsons:

An account of a B-24 plane crash on July 3, 1944

On July 3, 1944 the Miller Crew was returning to Muroc Army Base on the Muroc Dry Lake from a navigation training mission. It was just before midnight and the lights of the field and landing strip were in sight. Suddenly we lost fuel supply to one engine. The engineer adjusted the fuel control valve to “tank crossfeed to engines”, meaning that all tanks feed fuel to all engines. After a post-crash inspection it was determined that the fuel control dial was not properly positioned to the valve so that fuel was shut off to all engines.

Al Miller did a wonderful job of crash landing a powerless B-24 in the dark. Still, the plane broke up and was later dragged away in at least three sections.

The pilot and co-pilot were able to get out through the broken windshield. Swerzinski, the flight engineer, was pitched forward onto the control panel and died there. The nose gunner, Barber, was on the flight deck and suffered a broken back. The bombardier, radio operator, tail gunner, top turret gunner, and ball turret gunner were in the rear section of the plane with their backs against the bulkhead.

As navigator, I had just removed my headphones, left the nose area and had sat down on the bench in back of the pilot. I did not realize we had a problem and knew nothing of the impending doom. The impact knocked me out. When I came to, my crewmates were smashing the top turret plexiglass and I crawled out the opening. To this day, I have a lump on the back of my neck from the whiplash.

I was out of it and wanted to go back and get my navigation equipment. There was still a danger of fire so I refrained from doing that.

The tower knew there was a plane down but didn’t know where. We could see vehicle headlights scurrying around the dry lake looking for us. We had no flares so Al set fire to his parachute. We were three or four miles from the tower but they could see the fire.

Al was billed for the cost of the chute and I was billed for the lost equipment until the day we left the service.

Epperly, the bombardier, ran in his electric heated flying boots all the way to the tower and suffered severe blisters as a result. We all checked into the hospital. I stayed a couple of days. Within a week or so we had acquired two new crewmembers. Bill Waters was our new engineer and Bill Mitchel the nose gunner. The rest of the crew wanted to stay together and we were soon on our way to Italy.

This is my memory of a very harrowing experience. Given the start we had, we the survivors were very fortunate to live through 35 missions and return safely to the States.

Jim Parsons (navigator, December 2001)

This next recollection is that of Paul Verzella:

My name is Paul Verzella. I was radio operator, and gunner on Capt. Alvin Miller’s crew at Muroc, California.

On a long navigation mission we had flown to Milford, Utah on a round robin back to Muroc, flying at 10,000 ft when we got back close to Muroc, it was around 2 AM. I noticed a bit of excitement on the command deck. I saw the engineer say something to the pilot, then he went back to the fuel panel to check the amount of gas in the tans, then he went back to tell the pilot. About that time, I saw the landing lights come on, and I heard the engine roar. Not hearing crash landing instructions, because I was on liaison position on my radio calling Muroc on C.W. and I don’t remember going down. We had lost all four engines at the same time. We had no flaps and no landing gear. God must have been with us because we missed the top of the mountains and came down on a 45 degree slope. Just missed hitting the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

All four props tore off the engines and each one made circles going away from the plane. I remember none of the time the plane came down. Being that I did not hear instructions that we were going to crash, I didn’t fasten my seat belt. And in gunnery school we were told that the Martin turret would only stand 2G’s gravity before it tore loose from its mounting. When it did, it hit me in the back and knocked me from my radio operator’s seat, cutting my seat in two. Not being strapped in when it hit me, I ended up laying flat on the floor under the Martin turret.

We went a long way on our belly. I started to come to not realizing where I was or that we had crashed. Kind of in a daze. But it didn’t take long to find out because I could see out the radio operator’s window that the right wing was on fire. Then I heard the navigator saying that Skeetz was dead. He was pinned between the two coffin seats in a kneeling position with his head touching the top of the plane. The navigator and I thought for sure that we would die because the plane was on fire. As I lay under that turret, I remembered practicing in gunnery school that if we pulled the cable under the seat on the turret it would release the seat so the gunner could get out of the seat. I reached up and pulled the cable which allowed me to squeeze out from under the seat, so that I could crawl up into the turret. Meanwhile, the navigator and I discussed how we could get out through the top of the turret. I told the navigator that I would remove the ammo can next to him so that he could crawl up through the turret also. The moon was shining, I could see it through the dust-covered plexiglass. I could hear someone running on the fuselage and I yelled “break the glass, and we could crawl out”. Whoever it was trying to break the plexiglass on the turret hit me on the head because I was right under it.

The next thing I remember, the navigator and I were laying about thirty feet from the wrecked plane. We were a long way from Muroc, but we could see the lights from the base. I could see other planes flying over us flying in for a landing. One of them must have spotted us and reported we went down because we could see headlights going all over the desert looking for us. As I lay there seeing the lights wandering over the desert looking for us, I knew we had to get their attention somehow. I remember that the engineer kept a gallon of putt-putt fuel above the command deck over the bomb bay. I got up and ran over to the plane.

The ball turret gunner, Simpson, thought I must have been out of my mind trying to run back to the crash. He pulled me and I got loose and went into the plane and got the gallon of fuel, grabbed a parachute, and run from the plane with some chasing me. I opened the parachute, poured the fuel on it and lit it. The searchers came toward us like an arrow. The ambulance drivers told me to get on a stretcher. I felt all right, but they put me on a stretcher anyway. They brought Skeetz, our engineer, who was dead, and put him across from me in the ambulance.

When we arrived at the base hospital they took Skeetz body out first and I argued with the medics that I was all right and could walk. They decided to let me. The next thing I remember, going into shock and waking up the next day in the hospital. When I woke up, my pilot and the flight surgeon were standing beside my bed. The first thing I said to my pilot was that I’m not going to fly anymore, that’s it. He said that was up to me, but he was going to go up in the first plane he could and get the fear out of him. The flight surgeon asked me if he could touch me. When I asked him why, he told me that I was so lucky and if I got a chance to go out and see the wreck, not to because the turret had cut my seat in two and if I had it fastened I would have been cut in two. Well, I decided that I wanted to be a part of his crew. We were sitting in our tent waiting for two new members for our crew. A flight engineer replacement and the nose gunner who had his back broken in the crash. They asked why they were replacing people and they said “oh no!” When my pilot looked at the picture of the crash he told us “that was the best landing he ever made!”

And we went on to complete our tour of duty, from the Fifteenth Air Force base in Foggia, Italy.

Tech Sgt. Paul D. Verzella (December 2001)

The last memoir of this event is that of Frank Miller:

Recollections of Frank Miller regarding the crash at Muroc Army Air Field, 4 July 1944

This transcript by Roy Firestone, after a verbal interview with Frank on 30 January 2002.

Background: Frank Miller was 19 years old and the tail gunner on Al Miller’s B-24 Liberator bomber crew on the 3rd of July, 1944. The crew was on a navigational training mission that day, flying out of and returning to Muroc Army Air Field in California (now Edwards Air Force Base). The crew at this time consisted of the following men:

Al Miller, pilot, from ?, California

Lauri Ruha, co-pilot, from Iron Mountain, Minnesota

Leonard Epperly, bombardier, from Fayetteville, Arkansas

James Parsons, navigator, from Linwood Falls, New York

James Woods, top turret gunner, from Little Rock, Arkansas

? Baker, nose turret gunner, from ?

? Swerszinski, flight engineer, from Long Island, New York

Leland Simpson, ball turret gunner, from Barnhill, Illinois

Paul Verzella, radio operator, from Hookstown, Pennsylvania

Frank Miller, tail turret gunner, from Portland, Oregon

Says Frank:

I remember Skeets (Swerszinski) pretty well. He was about 21 and from Long Island, New York. He and I went to several places, a couple bars and restaurants, paling around a little.

Returning to the air field late on a clear, cold, well moon-lit night, I was in the waist section of the airplane. We were maybe 1500 feet up and about five miles from the runway. I don’t really remember the engines quitting but I knew something was wrong with the airplane, and I think I remember Al coming on the command line (radio) and saying something like “sit down, we’re going to crash.”

All I remember of the crash was the clouds of alkali dust and the hydraulic fluid that sprayed everywhere from the broken lines. Woods and I tried to get out the side of the airplane by throwing our shoulders against the plexiglass side windows – where the waist gunners are – and after three unsuccessful tries I hit the window right in the corner and went straight out of the airplane and onto the ground, with Woods right on top of me.

I saw a fire in one of the engines. I saw Woods and Epperly take off at a run towards operations to get help. I know there were other airplanes coming in on approach and Woods and Epperly had to run right across the active runway, so several pilots had to see them. I heard later that it was nearly half an hour before either of them could talk when they reached operations, due to the long run and the alkali dust they were breathing.

While we were waiting for help to arrive we watched as headlights in the distance were going in circles, looking for us. The fire in the engine was out by now, and I am not sure who put it out. I went back into the airplane for my parachute. Back outside I looked into the airplane from the front - it was crushed low enough to see into - and I saw Skeets dead, pinched between the pilot’s and co-pilot’s seats. His eyes were still open.

I checked the wind direction and I walked about 100 feet off the tail of the plane, unpacked my chute, took out my cigarette lighter, and lit the chute on fire to signal the rescue trucks.

I saw Baker walking around outside the plane in pain but it didn’t look to me like he was seriously hurt. In fact, I think it served his purposes well since he was not happy with having to fly combat and was removed from the crew after this.

When the fire and rescue trucks arrived a Major there wanted to know who had lit the chute, and I told him I did. He seemed more interested in that than anything else at the time, even though I told him I had to in order to get their attention.

Some bigshot investigators came out from Washington, DC to interrogate us. We were the 7th plane to crash that week there but the only one with survivors. They wanted to know why! And why did I burn government property? One Colonel wanted to court-martial me for it, but another asked him what he would have done in the same case, and it was dropped. It was a while before we flew again.

I remembered that just before this flight we had been on a two day pass and I was in Los Angeles with Skeets. When we came back to the base we saw a completely burned out B-24 at the end of the runway.

We got two new men for our crew after the accident: Wm. R. Mitchell, nose turret gunner, from Ft. Seybert, W. Virginia and William Watters, engineer, from Cochituma, Massachusetts.

There’s no doubt in my mind that Al did an amazing job of getting that plane on the ground on its belly and allowing most of us to survive the crash. We were also lucky to have the bright moonlight and the flat area where we hit. It really all happened so fast.